Labour is serious about immigration, and wants you to know it. To make sure you do, the government has embarked on a series of communications and policies. Adverts boasting about the number of people being booted out of the country1, videos of raids on the houses of migrants2, and a brand new policy stripping refugees of their right to citizenship3 all form part of Labour’s new direction on immigration. It is blindingly obvious that this direction reflects not any genuine conviction on the part of Labour, which started its period in government by bringing the Rwanda scheme to an end, but rather because it is worried about the electoral threat of Reform.

I will focus here not on the merits - or lack thereof - of the policies being pursued, which really is the important bit, but instead on this last component: political strategy. This is not because I lack a view on the former, but because I think the policy is being pursued largely due to incorrect assumptions on optimal strategy. The basic assumption underpinning Labour’s new strategy is that if it moves in policy terms closer to Reform, voters will no longer have a reason to vote for Reform. It is an attempt at realpolitik, supposedly rooted in hard-nosed realism about what is necessary for Labour to do to win in a new political epoch defined by Trump and Farage. However, as I have previously written4, the available evidence shows that this is likely to be misguided - the hard-nosed realism fails to engage the relevant empirical evidence and therefore to be realistic.

The political science literature shows us that social democratic parties perform best, or at worst are not harmed by, adopting liberal positions on social and cultural issues5. Among the reasons why this might be the case is that adopting the positions of far right parties on their core issues, such as immigration, typically helps rather than hinders these parties6. The mechanism underpinning this is that focusing on immigration makes it more important as an issue - but if immigration is the most important issue, it makes sense to vote for the party you associate with your stance on that issue. Voters associate hostile stances to immigration with the far right, and so when immigration is prominent as an issue, they vote far right. Moving closer to the views of these voters on immigration has the paradoxical effect of moving more, not less voters to the far right7. Voters looking for Nigel Farage won’t opt for diet Nigel Farage.

I Enter Frederiksen

A friend, who happens to be a political organiser, asked me if the example of the Danish Social Democrats contradicts this argument. In 2015 the party gained a new leader in Mette Frederiksen. It is hopefully not too much of a simplification to say that she moved her party’s position to the left on economics and in a conservative direction on immigration. Under her leadership the party performed well in the 2019 and 2022 general elections, and formed a minority government after the former, and a cross-ideological grand coalition after the latter. Notably, the far right Danish People’s Party (DPP) performed poorly in these elections and in recent elections to the EU parliament, at a time when other European far right parties have surged ahead in popularity.

I told my friend no: this example does not contradict the evidence in the political science literature. I recognised then, and now, that this answer will likely seem odd at first. I promised to write this post to explain my answer. Mark Leonard has however complicated the process of making my argument by publishing his own argument on the example of the Danish Social Democrats and its relevance to the UK Labour Party in the New Statesman8. This substack is neither a day job nor a side gig for me, and I am not particularly bothered to be scooped, so I will start by rehearsing the contents of Leonard’s article, most of which is built around the views of Martin Engell-Rossen, the strategist for the Social Democrats.

In some ways, Leonard’s account makes for comfortable reading for the architects of the Labour Party’s current approach. Leonard claims that the Social Democrat’s strategy sacrificed “cosmopolitan bourgeois” voters in the big cities in order to gain “working-class support” (back) from the DPP. In other ways however, it makes for difficult reading. Against the narrative I have set out above, Leonard claims that Fredericksen did not get “tough” on immigration per se. Instead, she accepted the moral obligation to accept refugees, while framing her opposition to “mass immigration” in terms of the Danish “social model”. In Fredericksen’s view, this social model could not survive mass immigration. In Leonard’s, the party successfully navigated the thorny issue of immigration by being authentic to its core values.

Engell-Rossen also emphasised the need for an authentically social democratic economic offer that makes clear what side of the clash between workers and bosses the party is on. As Leonard highlights, where the UK Labour Party avoids controversy, the Danish Social Democrats lean into it. So, Leonard’s answer to my friend is that things are not so simple as the Social Democrats moving right on immigration. What was important was an authentically social democratic policy offer on both immigration and the economy. There were important qualitative features of the Social Democrat’s electoral offering that we miss when thinking in purely spatial terms around the distance between the policies of parties and the preferences of voters.

II Events, dear boy, events

I am not only slow in having lost the race to Leonard in responding to my friend’s point, I am also slow in that other political scientists have beaten me to commenting on it. As Rob Ford has noted, one problem with Leonard’s argument on what the UK Labour Party can learn from the Danish Social Democrats is that sacrificing progressive voters is less risky for the Danish Social Democrats than the UK Labour Party9. This is because in Denmark’s PR system, if the Social Democrats lose progressive voters, these voters tend to end up voting for parties friendly to the idea of coalition with the Social Democrats. Shifting some voters to other left parties while gaining some voters from the right is a net gain for the left coalition. Labour has no such comfort: losing progressive voters has the potential end up costing seats, even if progressive parties collectively win more of the vote. The Danish Social Democrats can build coalitions external to their party: Labour cannot. It all depends on complex combinations of who votes where.

However, one of the benefits of my tardiness is that where before I was writing essentially for an audience of one, I can now join in the conversation around the Danish Social Democrats that Leonard has kickstarted. I think there’s another, more important critique of his article to be made, for which the starting point is that Leonard essentially takes Engell-Rossen’s interpretation of the Social Democrats’ success at face value. I think this leads him to reach fundamentally incorrect conclusions about what did and did not work in their strategy, and on what lessons the UK Labour Party should or even could draw from them.

Political outcomes are fundamentally characterised by what I am going to call contingency, but what might be called circumstances, and what was famously called events by Harold Macmillan. Basically: any given political actor has only very limited control over political outcomes. A party has access to certain levers with which it can improve its political prospects: it can change leader, it can opt for a new communications strategy, it can take new policy positions. If it’s in government, it has access to more levers, in that it can actually implement its policies and persuade voters to keep it in power through good governance. But there are many things beyond the control of political actors. Other parties can use the same levers to improve their prospects to your detriment, and events both domestic and abroad can dramatically change the political weather. As Liz Truss discovered (or would have, were she not busily denying reality), constraints on policy exist: you cannot, for instance, massively cut taxes without cutting spending and expect the markets not to respond.

A great deal of political analysis in my view basically forgets this simple fact. We treat winning strategists as political Nostradamuses, with profound insights into the deep secrets of winning elections. We treat those who lose accordingly, as fools who never should’ve been let near the levers of political power. Sometimes winners really are skilled strategists, sometimes losers really are useless idiots. But if we accept the role of contingency, of multiple causes of political outcomes beyond the control of political actors, then we cannot judge these things from political outcomes alone. Sometimes, the best possible outcome for a particular political party will be a less bad loss. And sometimes conditions are so favourable that a party can afford a few missteps it normally couldn’t and still go on to win the election.

To be clear, I’m not trying to suggest that Engell-Rossen has no idea what he’s talking about. Rather, my point is only that political actors do many things (like adopt conservative immigration policies) which they think exert causal effects that help them (by persuading voters to switch), but that we shouldn’t take their word for it on which ones actually do exert a causal effect - or in what direction. My working assumption that most paid party organisers are pretty good at working out what’s likely to work without the tools academics use (one day I’ll write something about this). But we shouldn’t take their word for it - better evidence is possible. The question that follows from all of this is how we do learn about causal effects relevant to party strategy - what does better evidence look like?

III An Alternative View

Back to my friend, and the reasons for my “no” answer. The specific question was whether the example of the Danish Social Democrats invalidated the argument I’ve set out from the academic literature. Let’s assume, temporarily, that it’s true that moving right on immigration enabled the Danish Social Democrats to win. The first version of the no, and in some ways the most important, is that political science draws its evidence from statistical models. And estimates from statistical models are averages. In this specific case, the estimate in the literature is the average relationship between social democratic party position and voter choice. To stress the point: the relationship estimated in a statistical model is an average of all the relationships that exist in each individual case in the data. Implicit in this formulation is that it’s entirely possible for the reverse relationship to be exist in some of the cases (e.g. in Denmark), but the overall relationship to be correctly estimated. This reason is why my “no” was almost automatic.

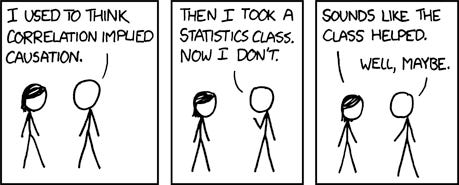

This begs the question: how do you work out if a particular case is different? We know, because of the role of contingency, that it isn’t outcomes that tells us. Most readers will, at some point in their lives, have come across the phrase “correlation does not imply causation”. Understanding what does imply causation is important for understanding what evidence would tell us that moving right on immigration helped the Danish Social Democrats win.

In statistics, you get a causal estimate of the effect of some X (such as social democratic party position on immigration) on some Y (vote choice) by holding other relevant variables constant. What this means is confounders. Consider the case of ice cream and sunburn. You know that ice cream doesn’t cause sunburn. But, you can imagine that ice cream consumption is correlated with sunburn. In this case, it being sunny outside both causes ice cream consumption, and causes sunburn. Failing to include the confounder in the statistical model means you estimate a causal relationship which doesn’t exist between eating and ice cream and getting sunburned.

A vast amount of the methodology of the quantitative social sciences is rooted in finding ways to get valid causal estimates of the effect of some X on some Y, simply because this is very hard to do with observational data and is always tentative until better evidence comes along. In the literature I mentioned earlier, the researchers estimated a causal effect of social democratic party position on vote choice. The details of how they did this are beyond my post here. The important thing to understand is that knowing a causal effect doesn’t necessarily improve our ability to predict outcomes. We can use an experiment to estimate the causal effect of a medicine on curing some disease - but in many individual cases, the patient who receives a medicine with good causal evidence behind it will still die.

IV Some Evidence

Outcomes in a single case at the case level (here the case level is Denmark) don’t tell us anything about causal effects in that particular case. And here comes the causation isn’t correlation bit: lots of things changed at the same time in the Danish example. I think it’s probably wishful thinking to say that the Danish Social Democrats didn’t move right on immigration. Adopting a position that accepts the notion that the Danish social model can’t survive “mass immigration” strikes me as making a concession to the right on immigration, even if qualitatively framed in social democratic terms. But the social democrats also obtained a new leader (and lots of things change at the same time when a leader changes, including perceptions of competence regardless of views) and moved left.

And this is just some high-level, abstract things that the Danish Social Democrats do control. Lots of other things probably happened, which one needs some level of contextual knowledge to be aware of, that impacted the 2019 and 2022 election results. To be clear, that isn’t me: I don’t have expertise on Danish politics. But one example of someone who does (other than Engell-Rossen) is Michael Ehrenreich, a Danish journalist. In an article for Project Syndicate10 he shares Leonard and Engell-Rossen’s view of the role of the Danish Social Democrats’ immigration-sceptical stance. But he also argues that the DPP holds highly unpopular policies on the environment (opinion polling suggests that the Danish public is strongly in favour of tough action to tackle climate change - the DPP is generally against such action) and on European security (the DPP argued the EU was not a valid forum for collective action on European security) which have held it back. There are lots of influences on voters at the same time, and the problem with associating the recent election outcomes with any single one of these is that anyone can cherry-pick their preferred explanation.

So, to answer the question I posed above: how can we get some answers specific to Denmark? The trick is to look for causal evidence in a study looking solely at what drives the vote choice of Danish voters. I used this trick in the case of the UK 2019 general election to establish evidence showing that Labour optimised its position on EU integration by being a broadly pro-EU party11. Fortunately for reaching a nice conclusion in this post, political scientists Søren Frank Etzerodt and Kristian Kongshøj did exactly that. In their paper12, they looked at survey data from the 2019 Danish general election, and examined several different beliefs and their effects on vote choice while controlling for other relevant variables (such as demographics). Their main finding is that vote-switching from the DPP to the Danish Social Democrats was driven by attitudes towards economic redistribution and welfare.

In other words: it is the changes in economic policy, rather than immigration policy, that drove the success of the Danish Social Democrats in the 2019 election in gaining voters from the DPP. Even more importantly for the broader argument in the political science literature, Etzerodt and Kongshøj show evidence that the Danish Social Democrats have failed to neutralise the issue of immigration, and that immigration as an issue still drives voters to the DPP or to other far right parties. Finally: they find no evidence to suggest that immigration attitudes mediate economic ones. The right-wing shift on immigration did nothing to help voters move over to the Danish Social Democrats on economic grounds. The short version is that the causal evidence on the 2019 Danish general election is completely in line with the more general evidence in the political science literature. This gets lost when we focus on outcomes alone, but to focus on outcomes in this way is to mistake correlation for causation.

V Coda

When I said no to my friend, I was certain about the first sense: that it was entirely possible for both the general finding in the literature to be valid, and for the opposite relationship to exist in a particular case. In the second sense, since I hadn’t yet seen Etzerodt and Kongshøj’s article, I only believed in the notion that it was potentially true that despite the observable outcomes of the Danish Social Democrats, moving right on immigration could still net harm their performance. The thing to understand is that, holding all else equal, the literature suggests that had the Danish Social Democrats not moved to the right, they might have done even better than they already did. At the same time, what the literature is not saying is that adopting a liberal social position means social democratic parties will win. It only means that holding other things constant, they will do better than they would otherwise do. That might still mean losing.

It is hard for political partisans to accept this lack of control. I’m sure a political psychologist somewhere has written something about this - if you’re aware of it, I’d like to read it. I want to conclude with a few thoughts. First: causal evidence is often highly tentative. It’s possible, even if unlikely, that in the future, someone will come out with new evidence which invalidates the current consensus in the political science literature. However, the important thing is that this evidence is the best we have right now. Because of the fundamental problems inherent in performing causal inference, we can never have greater certainty than a consensus around tentative evidence.

Second: too many social democratic organisers erroneously imagine themselves to be hard-nosed realists in adopting anti-immigration stances. Again, I am avoiding comment on the substantive policy component here. I have my (probably not very well-hidden) views, but it isn’t my area of expertise. However, I think that the open contempt a small selection of prominent Labour Party figures now hold for progressive opinion on social and cultural issues is probably an indication that they are mistaking what is essentially their own preferences for political realism.

Not much in political science is reassuring for social democrats, or for anyone, really. Things are generally too messy to give the neat answers political activists want, and contingency reigns in determining outcomes in a way that will forever defy the need for explanation so many of us feel. But on the far right, and electoral success, there is a rare slither of comfort for social democrats. Staying true to their own values is the most effective means of achieving the best possible electoral performance. The discomfort social democrats must face is that the best possible outcome just might not be winning.

Stacey, K. (2025) Labour launches ads in Reform-style branding to boast about deportations, The Guardian. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2025/feb/06/labour-launches-ads-in-reform-style-livery-to-boast-about-deportations [accessed 13/02/2025]

Maddox, D. (2025) Labour accused of trying to outdo Farage with migrant deportation videos, The Independent. URL: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/labour-reform-farage-immigration-raid-video-b2694954.html [accessed 14/02/2025]

Easton, M. (2025) UK to deny citizenship to small boat refugees, BBC News. URL: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c9d5wj9l8e2o [accessed 13/02/2025]

Abou-Chadi, T. and Wagner, M. (2019) The Electoral Appeal of Party Strategies in Postindustrial Societies: When Can the Mainstream Left Succeed?, The Journal of Politics 81 (4). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/704436

Abou-Chadi, T. and Wagner, M. (2020) Electoral fortunes of social democratic parties: do second dimension positions matter?, Journal of European Public Policy 27 (2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1701532

Abou-Chadi, T., Cohen, D. and Wagner, M. (2022) The centre-right versus the radical right: the role of migration issues and economic grievances, Journal and Ethnic Migration Studies 48 (2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853903

Krause, W., Cohen, D. and Abou-Chadi, T. (2022) Does accommodation work? Mainstream party strategies and the success of radical right parties, Political Science Research and Methods 11 (1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.8

Vasilopoulou, S. and Zur, R. (2024) Electoral Competition, the EU Issue and Far-right Success in Western Europe, Political Behaviour 46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09841-y

Meguid, B. (2008) Party Competition between Unequals. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511510298

Hobolt, S. and de Vries, C.E. (2015) Issue Entrepreneurship and Multiparty Competition, Comparative Political Studies 48 (9). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015575030

Leonard, M. (2025) Denmark shows how Labour can defeat the populist right, The New Statesman. URL: https://www.newstatesman.com/world/europe/2025/02/denmark-shows-how-labour-can-defeat-the-populist-right [accessed 13/02/2025]

Rob’s BlueSky post: https://bsky.app/profile/robfordmancs.bsky.social/post/3li3m4gzxvs2c

Ehrenreich, M. (2024) How Denmark Keeps the Far Right at Bay, Project Syndicate.

Swatton, P. (2023) Social democratic party positions on the EU: The case of Brexit, Party Politics 30 (5). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688231177557

Etzerodt, S.F. and Kongshøj, K. (2022) The implosion of radical right populism and the path forward for social democracy: Evidence from the 2019 Danish national election, Scandinavian Political Studies 45 (3). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12225